Table of Contents

Level of evidence hierarchy

When carrying out a project you might have noticed that while searching for information, there seems to be different levels of credibility given to different types of scientific results. For example, it is not the same to use a systematic review or an expert opinion as a basis for an argument. It’s almost common sense that the first will demonstrate more accurate results than the latter, which ultimately derives from a personal opinion.

In the medical and health care area, for example, it is very important that professionals not only have access to information but also have instruments to determine which evidence is stronger and more trustworthy, building up the confidence to diagnose and treat their patients.

5 levels of evidence

With the increasing need from physicians – as well as scientists of different fields of study-, to know from which kind of research they can expect the best clinical evidence, experts decided to rank this evidence to help them identify the best sources of information to answer their questions. The criteria for ranking evidence is based on the design, methodology, validity and applicability of the different types of studies. The outcome is called “levels of evidence” or “levels of evidence hierarchy”. By organizing a well-defined hierarchy of evidence, academia experts were aiming to help scientists feel confident in using findings from high-ranked evidence in their own work or practice. For Physicians, whose daily activity depends on available clinical evidence to support decision-making, this really helps them to know which evidence to trust the most.

So, by now you know that research can be graded according to the evidential strength determined by different study designs. But how many grades are there? Which evidence should be high-ranked and low-ranked?

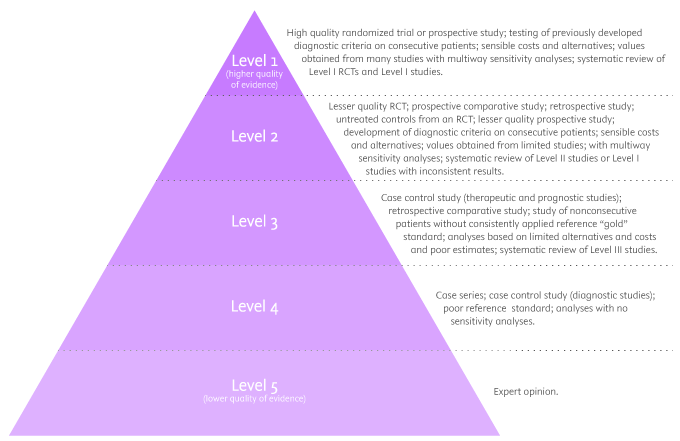

There are five levels of evidence in the hierarchy of evidence – being 1 (or in some cases A) for strong and high-quality evidence and 5 (or E) for evidence with effectiveness not established, as you can see in the pyramidal scheme below:

Level of evidence hierarchy

Level 1: (higher quality of evidence) – High-quality randomized trial or prospective study; testing of previously developed diagnostic criteria on consecutive patients; sensible costs and alternatives; values obtained from many studies with multiway sensitivity analyses; systematic review of Level I RCTs and Level I studies.

Level 2: Lesser quality RCT; prospective comparative study; retrospective study; untreated controls from an RCT; lesser quality prospective study; development of diagnostic criteria on consecutive patients; sensible costs and alternatives; values obtained from limited stud- ies; with multiway sensitivity analyses; systematic review of Level II studies or Level I studies with inconsistent results.

Level 3: Case-control study (therapeutic and prognostic studies); retrospective comparative study; study of nonconsecutive patients without consistently applied reference “gold” standard; analyses based on limited alternatives and costs and poor estimates; systematic review of Level III studies.

Level 4: Case series; case-control study (diagnostic studies); poor reference standard; analyses with no sensitivity analyses.

Level 5: (lower quality of evidence) – Expert opinion.

By looking at the pyramid, you can roughly distinguish what type of research gives you the highest quality of evidence and which gives you the lowest. Basically, level 1 and level 2 are filtered information – that means an author has gathered evidence from well-designed studies, with credible results, and has produced findings and conclusions appraised by renowned experts, who consider them valid and strong enough to serve researchers and scientists. Levels 3, 4 and 5 include evidence coming from unfiltered information. Because this evidence hasn’t been appraised by experts, it might be questionable, but not necessarily false or wrong.

Examples of levels of evidence

As you move up the pyramid, you will surely find higher-quality evidence. However, you will notice there is also less research available. So, if there are no resources for you available at the top, you may have to start moving down in order to find the answers you are looking for.

- Systematic Reviews: -Exhaustive summaries of all the existent literature about a certain topic. When drafting a systematic review, authors are expected to deliver a critical assessment and evaluation of all this literature rather than a simple list. Researchers that produce systematic reviews have their own criteria to locate, assemble and evaluate a body of literature.

- Meta-Analysis: Uses quantitative methods to synthesize a combination of results from independent studies. Normally, they function as an overview of clinical trials. Read more: Systematic review vs meta-analysis.

- Critically Appraised Topic: Evaluation of several research studies.

- Critically Appraised Article: Evaluation of individual research studies.

- Randomized Controlled Trial: a clinical trial in which participants or subjects (people that agree to participate in the trial) are randomly divided into groups. Placebo (control) is given to one of the groups whereas the other is treated with medication. This kind of research is key to learning about a treatment’s effectiveness.

- Cohort studies: A longitudinal study design, in which one or more samples called cohorts (individuals sharing a defining characteristic, like a disease) are exposed to an event and monitored prospectively and evaluated in predefined time intervals. They are commonly used to correlate diseases with risk factors and health outcomes.

- Case-Control Study: Selects patients with an outcome of interest (cases) and looks for an exposure factor of interest.

- Background Information/Expert Opinion: Information you can find in encyclopedias, textbooks and handbooks. This kind of evidence just serves as a good foundation for further research – or clinical practice – for it is usually too generalized.

Of course, it is recommended to use level A and/or 1 evidence for more accurate results but that doesn’t mean that all other study designs are unhelpful or useless. It all depends on your research question. Focusing once more on the healthcare and medical field, see how different study designs fit into particular questions, that are not necessarily located at the tip of the pyramid:

- Questions concerning therapy: “Which is the most efficient treatment for my patient?”

>> RCT | Cohort studies | Case-Control | Case Studies - Questions concerning diagnosis: “Which diagnose method should I use?”

>> Prospective blind comparison - Questions concerning prognosis: “How will the patient’s disease will develop over time?”

>> Cohort Studies | Case Studies - Questions concerning etiology: “What are the causes for this disease?”

>> RCT | Cohort Studies | Case Studies - Questions concerning costs: “What is the most cost-effective but safe option for my patient?”

>> Economic evaluation - Questions concerning meaning/quality of life: “What’s the quality of life of my patient going to be like?”

>> Qualitative study

Every kind of evidence is useful for the progress of science. Whether you are writing for the top of the pyramid or for its base, with Language Editing Plus Service you can achieve excellency in written text, impacting your readers exactly the way you aspire. Our team of language experts will pay special attention to the logic and flow of contents, adjusting your document to meet your needs. Apart from professional text edition, we offer reference checking and a customized Cover Letter. All this, with unlimited rounds of language review and full support at every step of the way. Use the simulator below to check the price for your manuscript, using the total number of words in the document.

Find more about Levels of evidence in research on Pinterest: